|

|

- Search

| Epilia: Epilepsy Commu > Volume 4(1); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are the basic treatment for epilepsy. Levetiracetam is known to affect the synaptic vesicle protein Sv2A, and its therapeutic range has been determined by experimental data and the literature. Considering the variability in clinical situations of each patient, or center-dependent, affecting seizure-free rate or adverse drug reactions, the subdivided therapeutic range of levetiracetam in epilepsy patients in a single center and their clinical characteristics were retrospectively analyzed in this study. Data were collected and retrospectively reviewed for patients who were diagnosed with epilepsy and visited the neurology outpatient center or were admitted to the Seoul National University Hospital from January 19, 2016 (when laboratory results for the concentration of levetiracetam began) to December 31, 2020. In this study, seizure freedom was achieved in >60% of all three groups with levetiracetam. Seizure-free rates tended to be higher with increasing levetiracetam concentrations; however, the statistical significance was not clear. The frequency of adverse drug reactions tended to be higher in the moderate- and high-dose groups than in the low-dose group, although this difference was not statistically significant. Further studies with multiple factors and situations with a larger number of patients will guarantee the detailed implications of levetiracetam concentration related to drug efficacy and adverse drug reactions in real clinical situations.

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are the basic treatment for epilepsy, and more than 20 kinds of drugs have been developed.1 Despite recent efforts for new drug discovery, approximately 30% of epilepsy patients suffer from drug-resistant, intractable seizures, even with multiple uses of AEDs. Other treatments, including surgical resection, ketogenic diet, and vagus nerve stimulation, can be used to treat drug-resistant epilepsy; however, some patients who are still not candidates for non-medical treatments have no choice but to carefully select multiple AEDs.2

While traditional AEDs are usually involved in the sodium channel, calcium channel, or γ-aminobutyric acid-mediated pathways, levetiracetam, one of the new generations of AEDs, is known to have an effect related to the synaptic vesicle protein Sv2A.3,4 Levetiracetam has linear pharmacokinetics, is excreted by the renal system, and is not metabolized by the hepatic system by cytochrome.5 In addition, it is known to have few drug-to-drug interactions compared to traditional AEDs, and clinicians usually do not have to adjust other AEDs when using multiple AEDs, including levetiracetam. Although the therapeutic range of levetiracetam has been determined by experimental data and literature, it can be variable in clinical situations of each patient, or center-dependent, affecting the seizure-free rate or adverse drug reactions.6-8

Thus, the subdivided therapeutic range of levetiracetam in epilepsy patients in a single center and their clinical characteristics were retrospectively analyzed in this study.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (No. H-2105-143-1220) with a waiver for informed consent and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data were collected and retrospectively reviewed for patients who were diagnosed with epilepsy and those who visited the neurology outpatient center or were admitted to the Seoul National University Hospital from January 19, 2016 (when laboratory results for the concentration of levetiracetam began) to December 31, 2020. The patients were diagnosed with focal epilepsy by experienced neurologists based on seizure semiology, electroencephalogram, and brain imaging such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

The concentration of levetiracetam was measured from the serum of the patient. To reach a steady state of levetiracetam, patients who had levetiracetam for more than 1 year without any change in dosing were considered for the analysis. Epilepsy patients who received monotherapy or polytherapy with AEDs were included in this study. To avoid unexpected effects of other medical conditions and intractable diseases, patients with seizures due to other medical conditions, such as infection, autoimmune diseases, vascular, or tumorous conditions, were excluded. Patients with uncontrolled underlying renal disease were not included in the analysis. Patients with epilepsy who had undergone treatments other than medical therapy, including surgical resection or other interventions, were also excluded. Patients in whom status epilepticus was not controlled, and clinical status could not be evaluated were excluded.

Clinical characteristics, 1-year seizure-free state, and any symptoms or signs related to adverse drug reactions at the time of serum sampling were analyzed. The seizure-free rate was calculated as the percentage of patients who achieved a seizure-free state for 1 year out of the total number of patients in each group. The proportion of adverse drug reactions in each group was calculated as the number of patients who experienced related symptoms and signs to the total number of patients in each group.

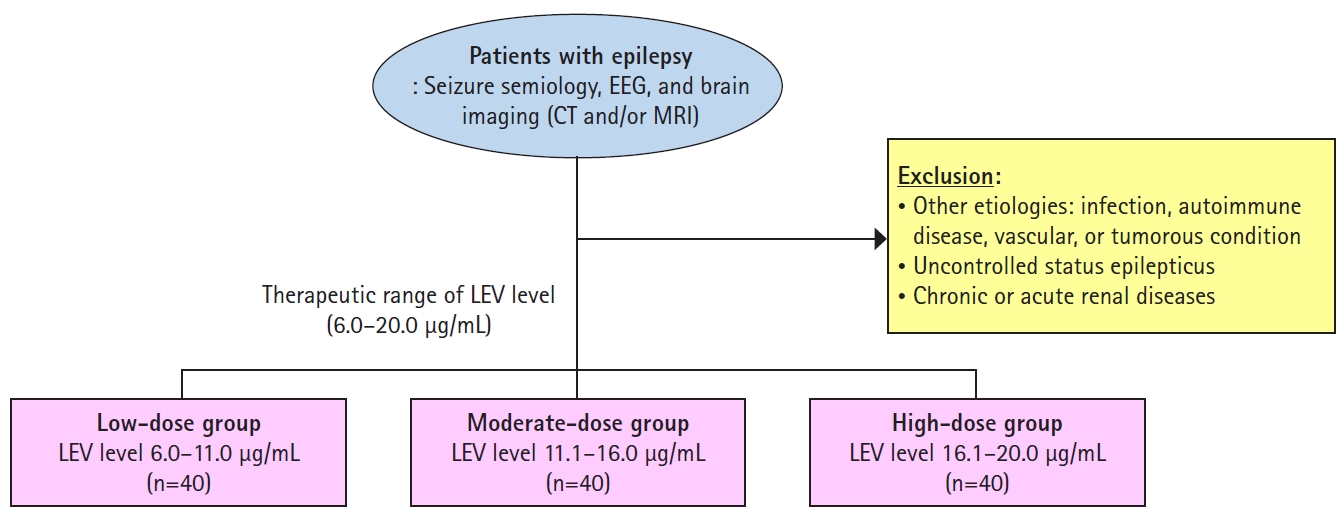

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 120 patients with epilepsy were included in the study. All patients showed good compliance with the prescribed AEDs. The median age of the patients was 43 years (range, 26–69 years) and 68 patients were female. The patients were categorized into three groups based on the concentration of levetiracetam: low-dose, moderate-dose, and high-dose (Fig. 1). Levetiracetam concentrations of all of the patients in this study were within normal range (6.0–20.0 µg/mL) as defined by the diagnostic laboratory department in the Seoul National University Hospital.

The median levetiracetam concentration, seizure-free rate, and proportion of adverse drug reactions in each group are shown in Table 1.

The most common adverse reactions related to levetiracetam in this study were dizziness, drowsiness, irritability, and aggression. Although the number of patients was not sufficiently large to evaluate statistical significance, the frequency of adverse drug reactions was higher in the moderate- and high-dose groups than in the low-dose group.

In this study, seizure freedom was achieved in >60% of all three groups with levetiracetam. Compared to other studies that focused on seizure reduction or seizure freedom based on dose and regimen of levetiracetam,9 this study showed a higher seizure-free rate (seizure freedom) within the normal range of levetiracetam concentration in serum. Seizure-free rates tended to be higher with increasing levetiracetam concentrations, as suggested by a previous study,10 although statistical significance was not clear in this study.

Based on previous studies, adverse drug reactions to levetiracetam include confusion, tremor, insomnia, suicidal ideation, bronchitis, upper respiratory symptoms, chest pain, dyspepsia, abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, gastroenteritis, arthralgia, rash, petechia, fever, fungal infection, gingivitis, otitis media, urinary tract infection, and weight gain.11 In a previous meta-analysis, the adverse event profile of levetiracetam did not show a clear dose-response relationship for significant adverse reactions.12 In this study, adverse drug reactions tended to occur more frequently in the moderate- and high-dose groups than in the low-dose group, although the statistical significance was unclear.

This study has some limitations. First, the time in which the sample of each patient was taken was variable and not controlled because most of the serum samples were taken from the outpatient center. The levetiracetam concentration did not reflect the peak or trough levels of the drug. Another limitation is that there was no consideration of changes in other AEDs in patients with polytherapy. Although levetiracetam is known to have little drug-to-drug interaction, the effects of other AEDs on levetiracetam due to changes in these AEDs might be overlooked in the study.

Further studies with analysis of the concomitant use of other AEDs, change in seizure frequency of each dose, and change in levetiracetam dose with a larger number of patients based on the trough level of the drug will guarantee detailed implications of levetiracetam concentration related to drug efficacy and severity of adverse drug reactions in real clinical situations.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of Epilia for their academic exchange and sincere support.

Fig. 1.

In this study, patients were categorized into three groups of low-dose, moderate-dose, and high-dose, based on the concentration of levetiracetam in the serum sample.

EEG, electroencephalography; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; LEV, levetiracetam.

References

1. Engel J Jr, International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE). A proposed diagnostic scheme for people with epileptic seizures and with epilepsy: report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2001;42:796–803.

2. Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010;51:1069–1077.

3. Dooley M, Plosker GL. Levetiracetam. A review of its adjunctive use in the management of partial onset seizures. Drugs 2000;60:871–893.

4. Klitgaard H. Levetiracetam: the preclinical profile of a new class of antiepileptic drugs? Epilepsia 2001;42 Suppl 4:13–18.

5. Noyer M, Gillard M, Matagne A, Hénichart JP, Wülfert E. The novel antiepileptic drug levetiracetam (ucb L059) appears to act via a specific binding site in CNS membranes. Eur J Pharmacol 1995;286:137–146.

6. Simister RJ, Sander JW, Koepp MJ. Long-term retention rates of new antiepileptic drugs in adults with chronic epilepsy and learning disability. Epilepsy Behav 2007;10:336–339.

7. Grant R, Shorvon SD. Efficacy and tolerability of 1000-4000 mg per day of levetiracetam as add-on therapy in patients with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2000;42:89–95.

8. Shorvon SD, Löwenthal A, Janz D, Bielen E, Loiseau P. Multicenter double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of levetiracetam as add-on therapy in patients with refractory partial seizures. European Levetiracetam Study Group. Epilepsia 2000;41:1179–1186.

9. Abou-Khalil B. Levetiracetam in the treatment of epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2008;4:507–523.

10. Rhee SJ, Shin JW, Lee S, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and dose-response relationship of levetiracetam in adult patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2017;132:8–14.